Hello Interactors,

We’re fully into Summer in the Northern Hemisphere, and as the earth tilts toward the sun, Interplace tilts toward the environment. And what a crucial moment to do so. Just last week, the Supreme Court made sweeping decisions that could unravel over fifty years of environmental legislation, threatening to plunge us into chaos. This upheaval comes precisely when our world’s natural boundaries desperately need regulatory stability and security to make any meaningful progress in combating global warming.

Let’s dig in…

POLLEN, POLLUTING, AND POLITICS

I recently returned from the Midwest visiting family. I like looking out of the airplane window at the various crop patterns from state to state. Trying to discern which state I was over; I was reminded of a corny Midwest joke.

Why do Iowa corn stalks lean to the east? Because Illinois sucks and Nebraska blows. Folks in Illinois tell the same joke, but it’s Ohio that sucks and Iowa that blows. You get the idea.

The truth is the wind does commonly blow from west to east oblivious to state borders. It sends whatever it wants across the border — clouds, dust, seeds, pollen…pollution. And if there’s money to be made, borders become porous or disappear altogether.

Those rivalrous corn jokes mirror an economic reality. Bordering states all compete for federal subsidies and access to markets — mostly across international borders. Access to these markets can be impacted by corn pollen drifting from one state to another.

With the widespread adoption of genetically modified (GMO) corn varieties, there’s potential for contamination of non-GMO corn fields by pollen from GMO corn fields on state lines. One study suggest cross-pollination could be detected up to 600 feet away from the source, although counts dropped off rapidly beyond 150 feet.1

But the more pressing concern isn’t pollen drift, but pollution drift. As part of the Clean Air Act, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has a “Good Neighbor” rule designed to reduce air pollution that crosses state lines. It requires "upwind" states to reduce emissions that affect air quality in "downwind" states which can cause significant health problems.

Last week, on June 27, 2024, the Supreme Court's ruling in Ohio v. EPA temporarily blocked this rule.

Fossil fuel companies and industry associations celebrated the decision as a win, viewing it as a check on the EPA's regulatory power. Meanwhile humans with a heart and lungs worry the decision leaves upwind states free to contribute to their neighbors' ozone problems for years.

It's worth noting that this is a temporary stay, not a final ruling on the merits of the case. The legal challenge will continue in lower courts, with the possibility of oral arguments as soon as this fall. But this ruling can also be seen as part of a pattern of the Supreme Court's conservative majority expressing skepticism towards federal regulatory authority, especially in environmental matters.

Take, for example, the ruling that came the very next day on June 28, 2024. The Supreme Court, in a 6-3 decision, curtailed EPA, and other executive agencies', power by overturning the Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council precedent. This shift endangers numerous regulations and transfers authority from the executive branch to Congress and the courts. Chevron has been a cornerstone in American law, cited in 70 Supreme Court and 17,000 lower court decisions.

The case began with fishermen challenging two similar rulings, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless v. Department of Commerce. These involved a 1976 law requiring herring boats to carry federal observers to prevent overfishing. A 2020 regulation mandated boat owners to pay $700 daily for the observers. Fishermen from New Jersey and Rhode Island, supported by conservative groups opposing the "administrative state," sued, arguing the law didn't authorize the National Marine Fisheries Service to impose the fee.

Adam Liptak of the New York Times reported the fisherman case was brought

“by Cause of Action Institute, which says its mission is ‘to limit the power of the administrative state,’ and the New Civil Liberties Alliance, which says it aims ‘to protect constitutional freedoms from violations from the administrative state.’”2

Liptak also reports these institutions are funded by Charles Koch, the climate change denying billionaire who has long supported conservative and libertarian causes.

It's curious how the Environmental Protection Agency came from a conservative libertarian and the first most dishonest president in my lifetime, Richard Nixon. The EPA will likely be obliterated should the least trusted former president get reelected — Felonious Trump.

GORSUCH'S GRIM GREEN GUTTING

I wrote about the formation of the EPA in July of 2021. 👇

“There was growing concern entrusting those very institutions responsible for the destruction of the environment with devising schemes to save it. The country’s air, water, and land were being smothered in waste. Something needed to be done. So, on July 9th, 1970, 51 years ago today [in 2021], the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was proposed by Republican President Richard Nixon.

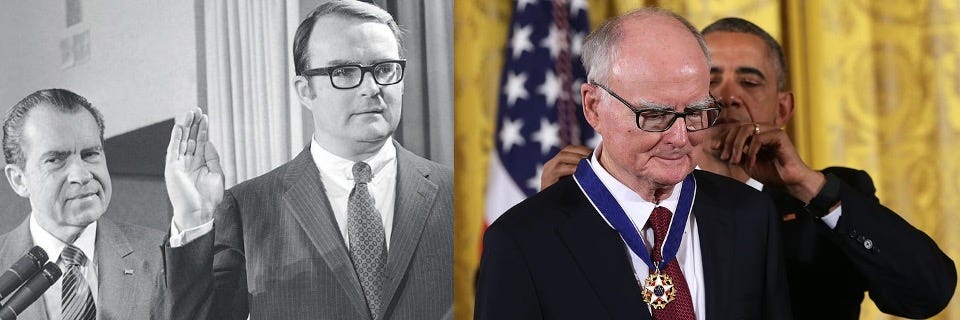

This agency was intended to focus on short-term fixes targeting violators of the law, so Nixon appointed Assistant Attorney General, Bill Ruckelshaus, to the post. Ruckelshaus promptly ordered a steel company to stop dumping cyanide into Cleveland, Ohio’s Cuyahoga River. It was so polluted that it had caught fire at least thirteen times. Ruckelshaus also banned the use of DDT.”3

Ruckelshaus served from 1970 to 1973 when he left public office to become a private environmental attorney. He was replaced by Russell Train who served as the second EPA administrator under Nixon and continued under another Republican President, Gerald Ford. During his tenure, he supported the expansion of EPA's international affairs, approved the catalytic converter to reduce automobile emissions, and implemented key environmental legislation.

Then came Douglas Costle, the EPA’s third administrator, serving under the Democrat President Jimmy Carter. His administration faced significant environmental challenges, including the Love Canal disaster and the Three Mile Island nuclear accident. One of the most notable achievements during his tenure was the creation of the Superfund cleanup program by Congress.

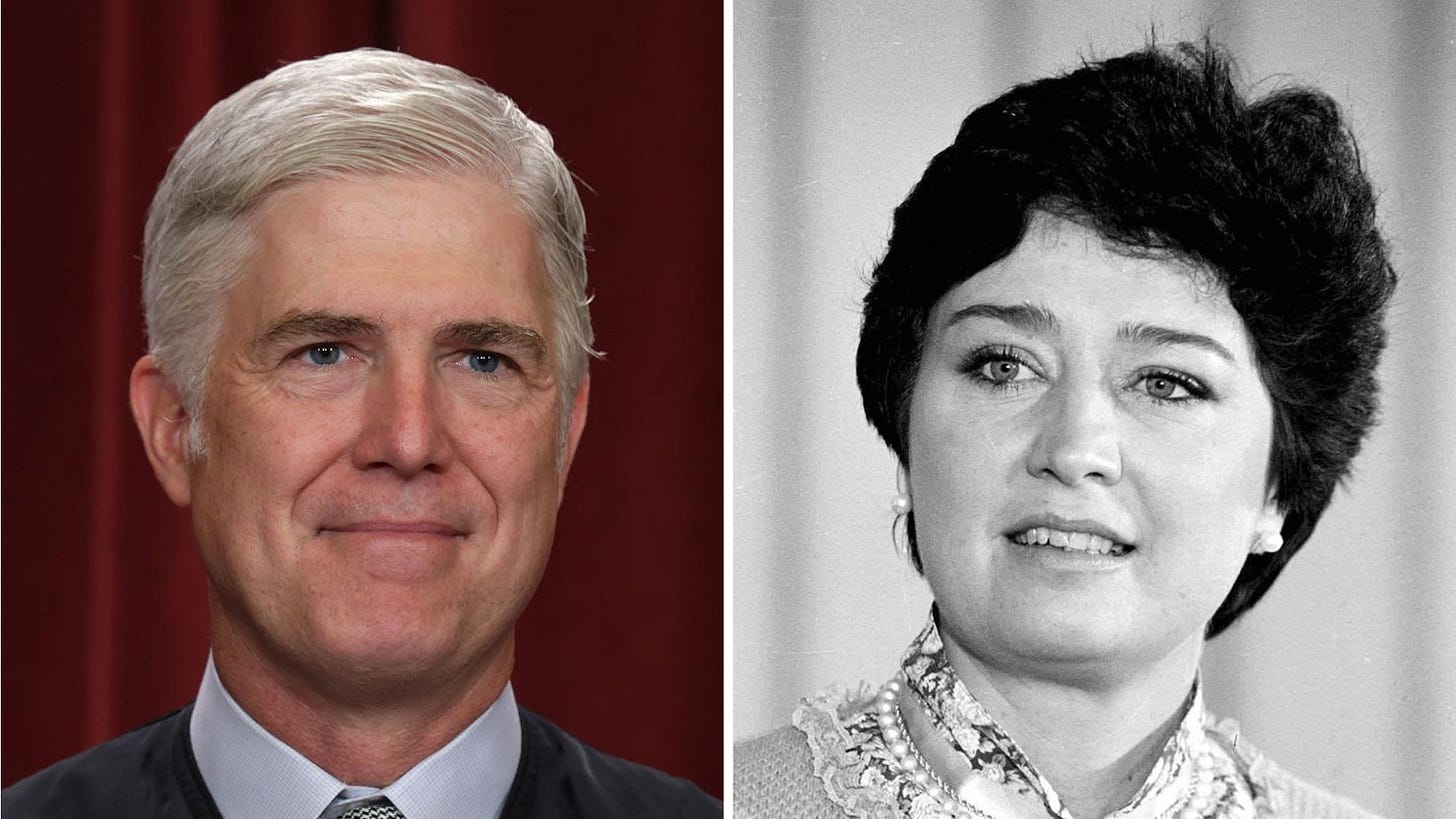

In 1981, Republican President Ronald Reagan appointed Anne Gorsuch Burford, current Supreme Court Judge, Neil Gorsuch’s mother. She was the first woman to hold the position but was forced to leave in 1983 amid growing controversy and concern.

Gorsuch slashed the EPA's budget by 22%, eliminating 3,200 personnel and reducing the agency's workforce by 30%.4 This raised concerns about the impact on environmental programs and staff morale.

Foreshadowing her son’s actions, she rolled back environmental regulations, like clean air and clean water rules and other environmental protections and decreased environmental enforcement cases. The number of cases filed from regional offices to EPA headquarters declined by 79%, and cases filed from the EPA to the Department of Justice dropped by 69%.5

Her approach to policymaking led to open conflicts with career EPA employees and several congressional committees investigating allegations of mismanagement of the Superfund program under her leadership6. The House voted to cite her for contempt of Congress for failing to turn over subpoenaed records related to the program[5].

Reagan couldn’t escape the fall out and forced her to resign in 1983, less than two years into her tenure. He then asked Ruckelshaus to return to his duties as head of the EPA. Ruckelshaus promptly fired most of her leadership team and got back to work protecting the environment running the EPA until 1985.

Nearly fifty years after being appointed by a Republican president to become the country’s first EPA administrator in 1970, fighting for environmental justice at the international, federal, state, local levels – and in the private sector – Ruckelshaus passed away at his home in my neighboring town, Medina, Washington in 2019.

And here we are, five years after his passing, with a Supreme Court intent on returning to the policies of Anne Gorsuch Burford with the help of a son who holds a grudge and a host of billionaire activists intent on institutionalizing libertarian law.

Neil Gorsuch not only joined the majority in a 6-3 decision to overturn the Chevron deference, he wrote a 33-page concurring opinion emphasizing the importance of this ruling.7 In his concurrence, Gorsuch stated,

"Today, the Court places a tombstone on Chevron no one can miss."

A cornerstone of environmental protection became a tombstone.

Perhaps hinting at his mother’s tenure and committing to his originalist interpretations of the constitution, Gorsuch argued that the decision simply means the courts will continue do ‘as exactly as it did before the mid-1980s, and exactly as it had done since the founding: resolve cases and controversies without any systemic bias in the government’s favor.’[6]

Gorsuch, like his mother, has long been a vocal opponent of the government siding with the protection of the environment, which he believes grants significant regulatory leeway to federal agencies over the judiciary.8 This opinion clashes with President’s Nixon (R), Ford (R), Carter (D), Reagan (R), George H. W. Bush (R), and Clinton (D) who all enthusiastically supported the need for agency oversight.

CONGRESS, COURTS, AND CLIMATE CHANGE

This ruling is seen as a significant shift in administrative law, potentially curtailing the power of federal agencies and changing how regulations are interpreted and enforced in the United States. Which is an administrative attitude that began with President George W. Bush.

His administration refused to advance a meaningful strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and opposed committing the United States to the Kyoto Protocol. He and his administration increased hostility towards climate science and resistance to significant policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

He prioritized economic considerations over environmental concerns, focusing on the potential costs of environmental policies. This approach marked a shift from the environmental legacy of his father and those before him, moving away from bipartisan cooperation on environmental issues that are unthinkable in today’s congress.

Optimists look at this ruling and claim it puts pressure on congress to write more specific and actionable legislation obviating the need for agency oversight or a need to go to court. The ruling could also clean up isolated cases of corruption between businesses and some government agencies.

But the EPA was created in part because members of congress lack the necessary scientific knowledge needed to write actionable legislation. Also, advances in science tend to outpace notoriously long legislative procedures. Besides, many members of congress today, especially on the Republican side, would rather not sponsor or partner on environmental legislation seeing it as a partisan issue.

I’m not advocating for more top-down government bureaucracy or believe federal agents necessarily always act in good faith, but this shift would transfer significant power from regulatory experts in agencies to judges. Given that many current Supreme Court judges tend to favor corporate interests, this shift likely weakens necessary regulatory oversight. Agencies, despite their imperfections, often have specialized expertise and are designed to protect public interests. Therefore, this transfer of authority to the courts may ultimately benefit large corporations at the expense of effective regulation and public welfare.

Looking back, the creation and support for the EPA reflected a broader trend in the tumultuous late 1960’s. The unease of the Viet Nam war coincided with the publishing of Rachel Carson’s literary environmental blockbuster, “Silent Spring”. The collective mood of the country yearned for solutions from environmental science to address complex environmental issues and their impacts on society. The creation of the EPA was a response to decades of rampant and highly visible pollution indicating that complex environmental problems required specialized agencies to address them.

But CO2 and other fine particulates and gasses wafting in the wind aren’t as visible as the smog of the 1970s. Nor are the effects of ozone depletion and acid rain of the 1980s. Now, with an activist Supreme Court with no term limits intent on weakening protective powers, we’re forced to breath the shifting winds of regulatory authority and environmental policy. In search of a view that embraces intention, action, and dynamism, I’m inclined toward Bruno Latour’s geophilosophy.

Latour’s Actor-Network Theory (ANT) underscores the agency of both human and non-human actors. It’s an approach that embraces the interplay between various entities—from legal bodies and industries to natural forces like wind and pollution—that shape our environmental reality.

The recent Supreme Court decisions, viewed through history and Latour’s lens, reveal a complex network where power is constantly negotiated and redistributed. The winds of the Midwest, carrying pollen or pollution across borders, symbolizes the intricate and often invisible connections that bind us. This includes regulatory changes that cross state and federal lines, impacting ecosystems and communities alike.

In this interconnected world, Latour reminds us that environmental and social issues cannot be compartmentalized or tackled in isolation. The rise of the Keeling Curve, recording raw and relentless increases in atmospheric CO2, serves as a stark reminder of the cumulative impact of countless actors and actions across the globe. It highlights the necessity for a holistic approach to environmental stewardship, recognizing the entangled nature of our existence.

Embracing Latour’s pragmatic realism, we best foster adaptive and resilient strategies, acknowledging the multiplicity of actors involved in environmental governance whether we like it or not. This perspective urges us to move beyond simplistic binaries of nature versus society, instead advocating for a collaborative effort to address the many crises we face. Until there’s a national bi-partisan rallying cry that unites divisions, we best integrate diverse voices and acknowledge the agency of all actors. Only then, in theory, can we better navigate the complexities of our environmental and social challenges and strive for a more sustainable, albeit ever changing, future.

Managing “Pollen Drift” to Minimize Contamination of Non-GMO Corn. The Ohio State University. Peter Thomison and Allen Geyer. 2024.

Supreme Court Overrules Chevron Doctrine, Imperiling an Array of Federal Rules. New York Times. Adam Liptak. 2024.

Ruckelshaus and Hickel Get us Out of a Pickle. Interplace. Brad Weed. 2021.

Remember When Neil Gorsuch’s Mother Tried to Dismantle the EPA? Slate. Lisa Hymas. 2017.

Ibid

Neil Gorsuch's mother once ran the EPA. It didn't go well. The Washington Post. Mooney, C., & Dennis, B. 2017.

Supreme Court strikes down Chevron, curtailing power of federal agencies. SCOTUSblog. Amy Howe. 2024.

Blockbuster Ruling Caps Justice Gorsuch’s Decades Long Quest to Kill Chevron. Bloomberg. Lydia Wheeler. 2024.