Hello Interactors,

Part 2 talks about the failures of borders, some recent alarming and revealing data about America’s ‘shared identity’, and some potential paths toward embracing the shaky state of states.

Let’s get into it…

NEWLY PROMISED LANDS

Part 1 left us at the Paris Peace Conference and Western-style cartographic geo-political mandates. Amidst these mandates was an admission by one leader that these arrangements would need subsequent alterations. Take this quote, for example:

“There are many complicated questions connected with the present settlements which perhaps can not be successfully worked out to an ultimate issue by the decisions we shall arrive at here.

I can easily conceive that many of these settlements will need subsequent reconsideration, that many of the decisions we make shall need subsequent alteration in some degree; for, if I may judge by my own study of some of these questions, they are not susceptible of confident judgments at present.”1

These are the words of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson in January of 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference. Sadly, ‘subsequent alterations’ over the last century have proven a tougher challenge than Wilson may have fully appreciated.

Whether his intentions were noble or not, rigidly draw borders on maps are obviously failing to truly encapsulate and represent the diverse and multifaceted spectrum of human communities — especially in a world where the negative effects of climate change know no such borders.

Could it be that identities and experiences resist being neatly delineated by Cartesian maps inherently based on political philosophies steeped in Cartesian dualities? Is it conceivable that nations and nation-states should not be confined to a singular, homogeneous identity?

Perhaps they are incapable of such definition. It may be these concepts have reached their limits. A suggestion that can compound feelings of uncertainty about what lies ahead in tumultuous times. This discomfort drives many to search for past eras that seemed more safe and certain — a time when there appeared to be a common shared national identity.

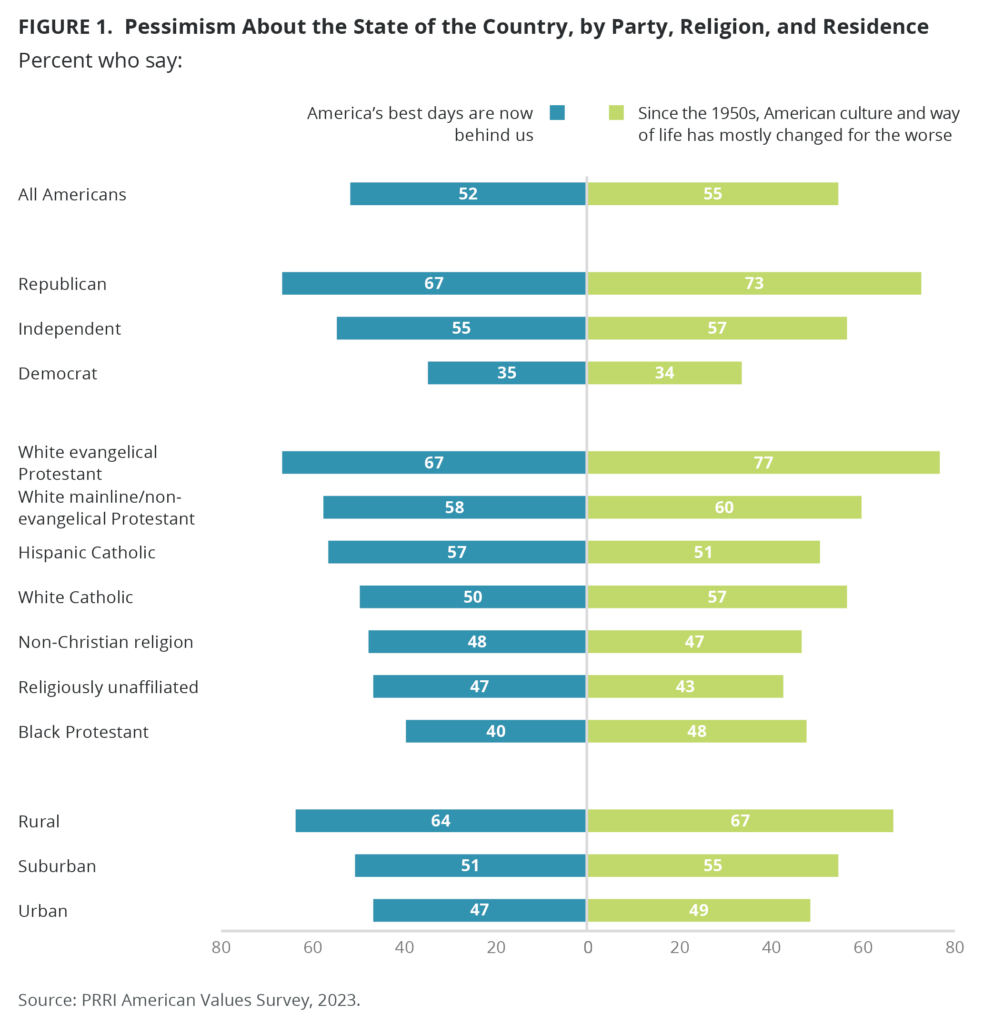

The Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) seeks such shared identities among those living in the United States in their annual ‘American Values Survey.’2 It’s one of the more respected surveys offering a pulse on American views of religion, culture, and politics. They recently released their 2023 results which can serve as one pulse on national identity. They project, based on their statistically valid sample, that

“Three in ten Americans (31%) agree that ‘God intended America to be a new promised land where European Christians could create a society that could be an example to the rest of the world.3 Just less than half of Republicans (49%) agree with this, compared with 26% of independents and only 18% of Democrats.”

PRRI data also reveals,

“Those who most trust conservative media (66%) and Fox News (54%) among television news sources are much more likely than those who choose no television source (29%) or mainstream media sources (24%) to agree that God intended America to be a new promised land.”

“Two-thirds of Republicans (66%) believe things have changed for the worse since the 1950s, compared with half of independents (50%) and only 30% of Democrats.”

The 1950s are often remembered as a time of economic prosperity, cultural growth, and the rise of the middle class in America. This era is seen as the embodiment of the 'American Dream,' with a booming post-World War II economy, expanding consumer culture, and significant advancements in technology and suburban living.

The period is characterized by strong family values, community cohesion, and distinct gender roles, often contrasted with the rapid social changes and complexities of modern life. Television, automobiles, and household appliances symbolize this era's progress and American ingenuity, reflecting a sense of unity and optimism about the United States' role in the world.

However, this romanticized view of the 1950s overlooks many critical social and political issues of the time, including racial segregation, gender inequality, and the fear and paranoia of McCarthyism. The decade, while remembered for its strong leadership and perceived lack of political division, also faced significant challenges.

The popular nostalgia for this era often represents a simplified and selective interpretation, failing to fully recognize the complexities and struggles that defined the 1950s, and inadvertently promoting a cartoonish, oversimplified version of history.

This difference in opinion is increasingly leading more Americans to embrace violence as a means of establishing a ‘shared identity.’

“Americans who believe that the country has changed for the worse since the 1950s are more than twice as likely as those who say that it has changed for the better to agree that true American patriots may have to resort to violence to save the country (30% vs. 14%).”

MAPPING THE AMORPHOUS

The idea “that God intended America to be a new promised land” is what many believe is the ‘shared identity’ representing the nation-state of America. It’s derivative of visions across centuries of European expansionism and colonialism prior to dominance of the United States of America as a nation and economic juggernaut.

Just as feudalism marked the beginning of a new social order and the political-economic apparatus of the nation-state, I wonder if our modern-day lords of geopolitical economic power are similarly controlling the toiling vassals and serfs — especially in regions with particularly low-wage labor.

The modern-day dynamics between the economically dominant Western and Northern Hemispheres offer metaphors to feudalism. Much like the concentration of wealth among feudal lords, powerful nations hold a significant portion of global wealth and resources, leading to pronounced economic disparities with less developed areas.

This situation mirrors the decentralized power structure of feudal times, where today's global landscape is fragmented, with Western and Northern countries wielding substantial influence, creating varying levels of power and development worldwide.

The strong economic and political alliances within these hemispheres, akin to feudal loyalties to local lords, often exacerbate global divisions leading to patterns of regional allegiances and wider communal divides.

Furthermore, the influence exerted by these dominant regions over global policies, economic trends, and cultural norms is reminiscent of the control feudal lords had over their territories. They shape international trade, governance, and cultural exchanges in ways that echo the hierarchical and power-centric nature of feudal societies. This power and dominance, under the guise of a ‘shared identity’ is then used as leverage in exchange for military and monetary protection for survival.

Survival was very much on the minds of those living through the 15th-17th centuries. Generation after generation witnessed catastrophic meteorological events brought on by the Little Ice Age. This had devastating impacts on people around the world and played a significant role in shaping the social, political, and economic structures that followed. Might we be on the verge of a new world order?

Survival is also on the minds of those suffering the travesties of wars nation-state border disputes create. Including those living the through the lead up to and aftermath of World War I and World War II.

I wonder how those feelings of uncertainty compare to feelings of uncertainty today. Scholar, podcaster, and fellow Substack writer Christopher Hobson recently reflected on quotes from intellectuals struggling to make sense of the aftermath of World War I and II. Here’s a quote from the 1922 Austrian writer, Robert Musil, in his book ‘Helpless Europe: A Digressive Journey’ that could just as easily be written today.

“And so we arrive at the present day. The life that surrounds us is devoid of ordering concepts.”4

Cartesian maps of nation-states are politically charged, legally binding ordering concepts, but their certainty is imagined. When Woodrow Wilson cautioned the agreements at the Paris Peace Conference are "not susceptible of confident judgments" he was suggesting the matters in question were too intricate, uncertain, or evolving to allow for definitive, confident decisions.

Wilson is indicating that, due to the complexity and fluidity of the issues, any judgments or decisions made during the conference might be provisional and subject to change.

Let’s consider some alternatives traditional mapping of nation-states.

Could psychogeographic maps, reflecting the emotional landscapes of diverse groups, provide a more nuanced understanding of human geography?

Perhaps powerful nations and states should be leading exercises in participatory mapping offering communities themselves more accurate and meaningful representations of their own spaces and identities.

Maybe counter-mapping or decolonial mapping practices that challenge the established narratives and power structures inherent in traditional cartography could offer new perspectives to those so sure of a ‘shared identity’?

Critical Geographic Information Science can reveal underlying patterns of inequality and socio-political dynamics commonly overlooked, shifting conceptions of what could be?

And in a world increasingly influenced by feminist perspectives, how might feminist cartography reshape our understanding of spaces and places, especially in relation to gender dynamics?

These questions, rooted in the alternatives to Cartesian cartography, invite us to consider new paradigms in mapping and understanding of human geography. They are emerging as new tools just as anthropography was emerging at the time of the Paris Peace Agreements.

We are clearly in need of a new shared understanding that could offer new directions in our politics, economics, and global societies, but we should heed the advice of Woodrow Wilson and be cautious of our confidence.

Christopher Hobson encourages mindfulness and carefulness as we attempt to make sense of what comes next. He suggests we

“…resist the lure of comfortable frames and easy explanations, and instead to fully reckon with ‘the brittleness of the world’ and what potentialities might be present in these conditions.”5

Perhaps it’s best to embrace the shaky state of states and the ambiguity of the unknown as we try to make sense of the state of our world. As Hobson offers,

“The post-Cold War era has passed, (hyper)globalization has peaked, the unipolar moment has finished, neoliberalism has perhaps entered its zombie phase.”

We live in…

“A time defined by what it is no longer, what is ‘not quite here, but yet at hand’.”

Woodrow Wilson, Address to the Peace Conference in Paris, France. The American Presidency Project. UCSB.

Threats to American Democracy Ahead of An Unprecedented Presidential Election. Findings From The 2023 American Values Survey. PRRI. 2023.

It’s important to note the use of language. This statement, and this survey in general, may not only be measuring a point in time, but inducing some to adopt these beliefs as their own. Like a thermometer that induces a fever.

Resisting kitsch analysis: The old and the new. Imperfect Notes. Hobson. 2023.

Ibid