Hello Interactors,

This is the last post of the Spring 2021 cartographic portion of Interplace. My recent trip to Kansas City got me thinking about the role land use mapping and planning played in the formation of select surrounding suburbs.

It’s also a bit of a teaser for the Summer season as Interplace moves toward the environment, physical geography, and its role in urban planning and design.

As interactors, you’re special individuals self-selected to be a part of an evolutionary journey. You’re also members of an attentive community so I welcome your participation.

Please leave your comments below or email me directly.

Now let’s go…

LIFE AT THE BOTTOM OF THE SACK

One glance out the window as you fly into the Kansas City airport and the gridding of American land becomes apparent. A array of crops, fields, and irrigation circles all stitched in and bordered by hard edged polygons but also gently meandering rivers and streams. It’s all part of the grand plan to divide the organically occurring hills and valleys of America into artificial two dimensional polygons. A tapestry of maps for settling colonists that doubles as a ledger for settling government’s finances.

The patterns are apparent at the street level too. The main arterials are uniformly distributed and connected at intersections; east-west and north-south thoroughfares that reach far beyond the core of the city. But just off these axes of expansion are sweeping tree lined curvilinear roads featuring large deciduous trees with canopies of leaves floating over a pool of manicured Kentucky bluegrass. And nestled within are the beloved single family homes. A community planned from above on a map that sells an illusion of a naturally occurring pastoral ideal. A residential product planned, designed, and manufactured for settling White suburban colonists. Like me.

I grew up on a cul-de-sac in a planned community in Norwalk, Iowa. It doesn’t get anymore suburban than a cul-de-sac. I admit, it was nice. The center of the street featured a domed grassy circle that the neighborhood kids would all use to play kick-the-can. We’d place the can atop the center of the mound and then run and hide behind the surrounding houses and bushes. Cul-de-sacs are great for families because they’re dead ends. The literal French translation is ‘bottom of the sack’. The only cars, which was rare, were driven by the parents of the kids playing in the street. Parents of this generation knew the benefits of playing in the road because it was a lawful thing to do when they were kids. But with the rise of the automobile came laws that made it illegal to play in the street. Sadly, it still is.

Our little cul-de-sac was part of Norwalk’s first annexation; just four years after I was born. After we had all grown, my parents moved to Overland Park, Kansas to retire. Overland Park was founded around the same time Norwalk was incorporated in 1905. And like Norwalk, its founding was driven by the railroad, but its expansion was driven by the automobile. The growth of roads in suburban America correlates with the annexation of land throughout the 50s and 60s. Favorable home loans from the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) helped too. As did redlining – the discriminatory delineation of red lines on ‘residential security maps’ where home loans were denied due to the area resident’s racial and ethnic origins.

Overland Park annexed developments for decades making it the second most populous city in Kansas (behind Wichita). This area of Johnson Country was developed primarily by the Kroh Brothers Development Company after World War II. They, like the more famous area developer J. C. Nichols, were deemed “community builders” and benefited from building subsidies flowing from the FHA. But the communities they were building were strictly White. Using harsh racist covenants and deeds, they controlled who could buy homes in these suburbs.

Here’s how the deed read for Leawood Estates, a community that shares the eastern border of Overland Park.

“None of said lots or portions of lots shall ever be sold, conveyed, transferred, devised, leased or rented to or used, owned or occupied by any person of Negro blood or by any person who is more than one-fourth of the Semitic race, blood, origin, or extraction, including without limitation in said designation, Armenians, Jews, Hebrews, Turks, Persians, Syrians, and Arabians, excluding, however, from the application of this paragraph partial occupancy by bona fide domestic servants employed thereon.”

EBENEZER’S POLAR PLUNGE

These satellite cities just beyond the reach of the city are associated with the post war rise of wealth and the automobile. But this method of mapping and planning had been around much longer. Ebenezer Howard introduced the concept of a ‘Garden City’ in 1895 in England in response to the overcrowding, congestion, and pollution that came with the industrial age. It’s a method of city planning that was cross-referenced by the City Beautiful Movement found in Chicago’s Burnham Plan.

Howard himself had lived in Chicago working as a reporter before returning to England. He was a writer, not an urban planner or architect. His Garden City vision was inspired by a science fiction utopian novel called, Looking Backward: 2000–1887 by American Edward Bellamy. It’s a story that starts in the year 2000 in an America that had morphed into a socialist utopia. It was in response to the rising wealth, power, and control of overreaching monopolists and oligarchs that had been taking hold in America in the late 1800s. It may be a good time for us all to be looking backward to Bellamy. Just this week Lina Khan was confirmed as the Chair of the Federal Trade Commission — a bi-partisan appointment to an agency that enforces antitrust law by a woman with a reputation for going after oligopolies. Read more about the significance of the appointment of this progressive woman in Matt Stoller’s piece here.

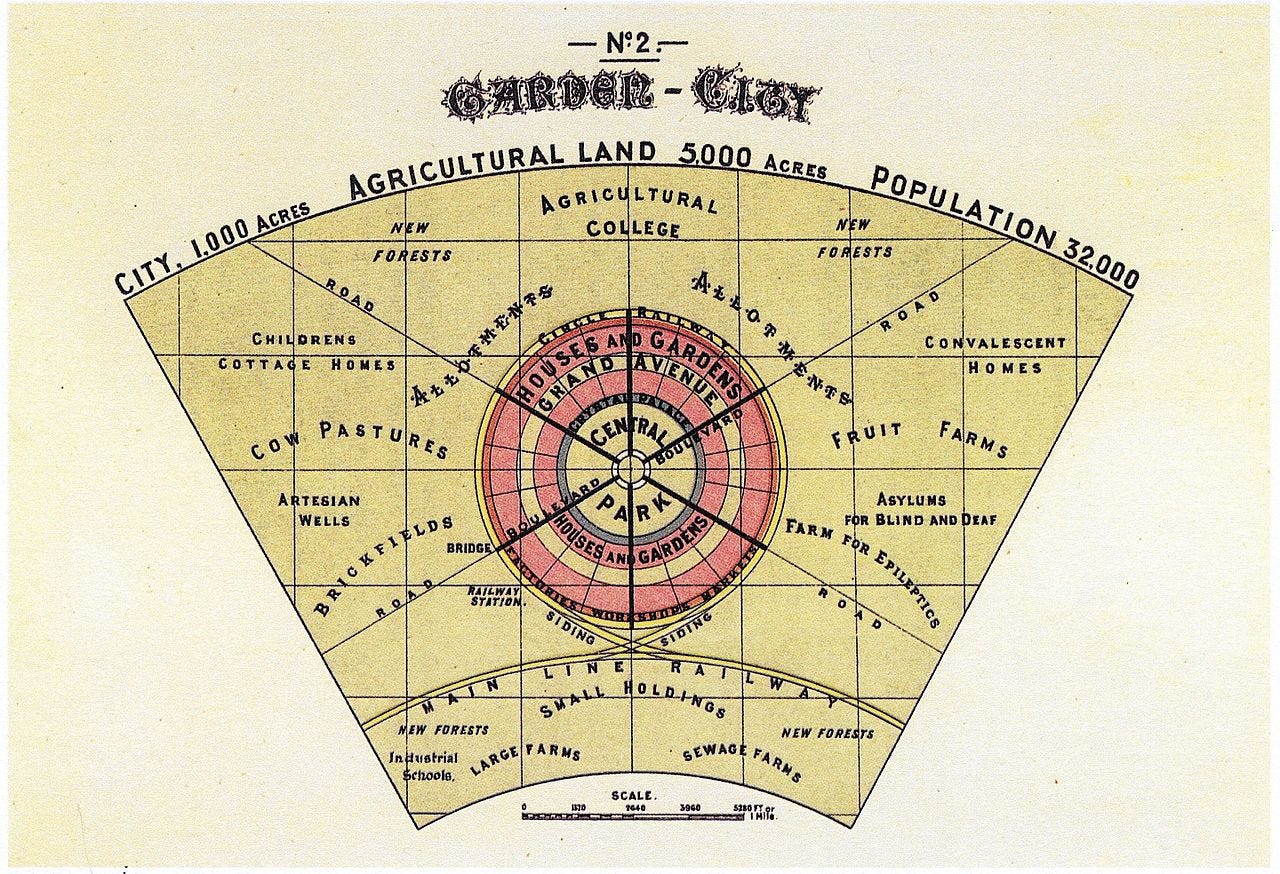

Howard’s vision for Garden Cities was amplified by his diagrammatic conceptual maps that accompanied his utopian ideas in his 1898 book Garden Cities of To-morrow. In keeping with the European cartographic tradition of fixed, top-down, graphical and mathematical overlays atop a morphing organic landscape, he advocated not for a gridded Cartesian plan, but a circular arrangement along polar axes. His idea was to plan self-contained smaller circles of cities around a larger central city all connected by rail creating what he called a “Group of Slumless, Smokeless Cities.”

Like his contemporaries, and many today, his view was that the earth is here to be exploited and controlled. In keeping with industrialist and neo-liberal capitalist traditions, he believed the earth to be an endless well of resources and the duty of the White man was to coerce or seize control of the ‘savages’ that had tended to it in reciprocity for millennia. Here’s Howard in his book Garden Cities of To-morrow,

“The planet on which we live has lasted for millions of years, and the race is just emerging from its savagery. Those of us who believe that there is a grand purpose behind nature cannot believe that the career of this planet is likely to be speedily cut short now that better hopes are rising in the hearts of men, and that, having learned a few of its less obscure secrets, they are finding their way, through much toil and pain, to a more noble use of its infinite treasures. The earth for all practical purposes may be regarded as abiding for ever.”

The countryside, with “land laying idle”, was one of the attractions Howard envisioned for his satellite cities. He created a diagram illustrating what he believed were three magnets influencing people’s decisions on where to live and work. The three magnets were Town, Country, and Town-Country. Each magnet included words that described the benefits and detractors of each. Town’s were rich in attractions, but was also full of ‘Slums’ and “Gin Palaces”. The Country “Lacked Amusement” and “Long hours and low wages” but was home to “Wood, meadow, and forest” that was in “Need of reform”. The Town-Country provided the best of both worlds:

“Beauty of Nature, Social opportunity. Fields and Parks of Easy Access. Low rents, High wages. Low prices, no sweating. Field of enterprise, Flow of capital. Pure air and water, Good drainage. Bright homes and gardens, No smoke, No slums. Freedom. Co-operation.”

Sounds pretty good. Utopian, almost. No such utopia has ever been accomplished, but Howard’s ideas continue to inspire designers today. In 2014, British urban design firm, URBED, won the Wolfson Economics Prize for their envisioning of a modern-day garden city, Uxcester.

FEDERAL FINANCING FIX

Howard was intent on making the Town-country attractive to lure people who abandoned the countryside for jobs in the city.

“Town and country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilisation. It is the purpose of this work to show how a first step can be taken in this direction by the construction of a Town-country magnet; and I hope to convince the reader that this is practicable, here and now, and that on principles which are the very soundest, whether viewed from the ethical or the economic standpoint.”

The Kroh brothers were convinced and saw country “land laying idle” just outside the an increasingly over-crowded Kansas City. They also had visions of a “new civilization” for White residents. But ethical? I don’t think so. Economic opportunity? Absolutely. Long before they set out to plan and build their White suburbs, Kansas City and the U.S. Federal government were already fashioning their own magnets.

As Tulane University’s Director of Urban Studies, Kevin Fox Gotham, writes in his paper, Missed Opportunities, Enduring Legacies: School Segregation and Desegregation in Kansas City, Missouri,

“From the 1920s through the 1950s, the Kansas City Real Estate Board (formed in 1900) subscribed to a national code of real estate ethics that endorsed the view that all-black and racially mixed neighborhoods were inferior to all-white homogenous neighborhoods.”

“During this time, the FHA's Underwriting Manuals referred to the "infiltration of inharmonious racial or nationality groups" as "adverse" to neighborhood stability and advised appraisers to lower the rating of properties in racially mixed or all-black neighborhoods. Although the FHA removed explicitly racist language from its manuals in the 1950s, later manuals continued to refer to the necessity of maintaining "homogenous" neighborhoods and warned of the risk of "dissimilar" groups as "unstable" and "inharmonious".”

Between 1934 and 1962 the FHA insured more than seventy-seven thousand homes in the Kansas City area, but just one percent of them went to Black families. In another paper entitled, Race, Real Estate, and Uneven Development, Gotham quotes a mortgage company president who was Chairman of the board from 1934 to 1965,

“The FHA and VA wouldn’t insure any guarantee loans [in the Kansas City area] unless there was a [racial] restriction involved, and most lenders on residential property were relying heavily upon the FHA and VA for their protection. So that as long as that remained their position, the lender really had no choice but to observe the restriction.”

With local and Federal Government on their side, the Kroh brothers could confidently conjure and craft curvaceous cartographic corridors and cul-de-sacs atop a topographic map of the Kansas countryside. A green garden suburb made up of White people. Their plan also coincided with federal laws dictating the geometry of street design. Streets wide enough to accommodate free parking and a fast flow of traffic, connected curb-cut driveways leading to a garage connected to a cookie-cutter home who’s design was pre-approved by the FHA to streamline bulk lending processes. The Kroh brothers may have been called “community builders”, but it wasn’t so much a community that was being built, but a pre-packaged residential product that was being sold to White people seeking a “new civilization.”

The Kansas City area remains highly segregated to this day. Mostly down the north-south racist dividing line of Troost Avenue. But it wasn’t always that way. In 1950 seventy five percent of the population east of Troost was White. By 1970 that area dwindled to 25 percent. Over ninety-two thousand White people fled to the west side of Troost while nearly sixty-two thousand Black residents moved to the east side. There were, and are, many contributing factors to these facts like skewed school segregation schemes, self-segregation, job availability, and, of course, generations of lucrative loans guarantees to White people.

It’s not clear where race and ethnic origin fit in Ebenezer Howard’s ideas for a garden city utopia. But he did envision idealized democratic communities that were planned and structured in a way as to eliminate social divisions. There is no question people of all races and ethnic origins would like opportunities to live in a idyllic garden suburb. Maybe even on a cul-de-sac featuring a grassy domed circle where children of mixed heritage could race to kick the can.

Given America’s founding fathers believed the United States to be an ongoing democratic experiment for humanity at large — a country that has long beckoned the tired, poor, huddled masses yearning to breathe free — perhaps we should all take a piece of Ebenezer Howard’s idealism to heart as we seek equitable access to housing in towns of all sizes and locations:

“Besides, as those persons who migrate to the town are among its most energetic and resourceful members, it is but just and right that their more helpless brethren should be able to enjoy the benefits of an experiment which is designed for humanity at large.”